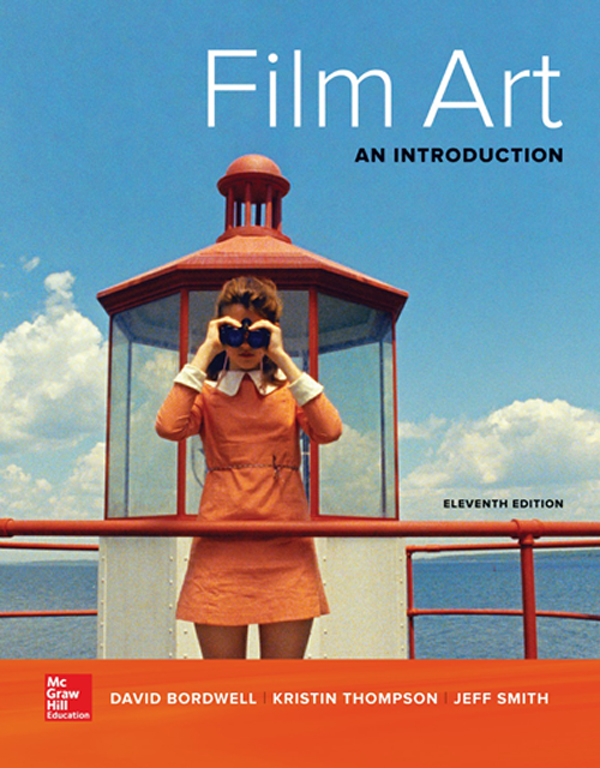

Film Art an Introduction David Bordwell and Kristin Thompson 11th Edition 2017 Mcgraw Hill Pdf

DB hither:

Twoscore years ago, Kristin and I signed a contract with Addison-Wesley publishers to write Film Art: An Introduction. The first edition, a squarish detail with a butterscotch-chocolate-brown cover, was published in 1979. Like about textbook authors, we had to assign all rights to the publisher. Addison-Wesley sold our book to Knopf, which produced a second edition in 1985. And then the book was caused by McGraw-Hill. McGraw-Loma published the subsequent nine editions, from 1990 onward.

Last week, Kristin and I and our new collaborator Jeff Smith received our copies of the eleventh edition. It looks very good and we call up it's our best endeavour notwithstanding. By chance, we learned at the aforementioned time that Film Art, in all its editions, currently ranks as 153 in books assigned in American college courses (based on a sample of almost a meg syllabi). No other film textbook appears in the top 400 titles. Back in the 1970s nosotros never imagined such success.

FA 11e contains many new features, which I'll talk about shortly. Simply I'd also like to say some things near the book's perspective on cinema. I've discussed the conceptual side of our approach in an entry devoted to the previous edition.

Merely since concepts don't ascend from naught, I thought I'd wax a little personal and talk almost how Film Art has reflected my developing ideas about movies. Readers wanting the meat-and-potato information about the new edition can skip down to the section, "Humblebragging, minus the humble part."

A bookish moving picture wonk

Living on a subcontract, I was somewhat isolated, but I did see Hollywood classics on television, and I could occasionally catch current releases at theatres in nearby towns, notably Rochester, NY. With the aid of Andrew Sarris'southward "American Directors" result of Picture Civilization and some problems of Movie (UK), my high-school years became devoted, in role, to moving picture.

During the 1960s, involvement in film exploded. Europe's "immature cinemas" similar the French New Moving ridge came to prominence. Hollywood films became edgier. High-tone magazines began to pay attention. This was the era in which James Agee, Parker Tyler, and Manny Farber gained somewhat delayed fame as critics. (I talk about this evolution in my Rhapsodes book.) Cahiers du cinema became known outside France, and American critics like Sarris and Pauline Kael became artworld celebrities.

In the same era in that location came a outburst of film-appreciation books. They weren't textbooks per se, but they were often used in the pic courses that were springing upwards across the land. Among those books were Ernest Lindgren's The Fine art of the Film (rev. ed., 1963), Ivor Montagu'south Film World (1964), and Ralph Stephenson and J. R. Debrix's The Cinema as Art (1965). I was fatigued to the thought of a full general account of the possibilities of film as an fine art course, and then these books, followed past V. F. Perkins' contrarian Motion-picture show as Moving-picture show (1972), appealed to me. I later realized that they belonged to a genre that stretched back to the 1920s and included extraordinary contributions like Renato May's Linguaggio del Flick (1947). Still further back, they, like all texts, owe a debt to Aristotle'southward Poetics and Renaissance treatises on the visual arts.

Before the 1970s, most higher flick courses were organized historically, running from Lumière/Méliès/Porter to Neorealism. (Arthur Knight again.) But there was emerging a different sort of grade, one that surveyed "the language of film" conceptually. Just equally an introduction to music would lay out basic categories like tune, harmony, rhythm, and form, so film courses—in the way of the aesthetics surveys I mentioned—would endeavor to isolate the bones elements of cinema. This new orientation was probably besides inflected by semiotics, then becoming a hot topic in grad-school circles.

When I came to UW—Madison in 1973, ABD and eager to work, I was given the basic survey form, Introduction to Film. It enrolled near 400 students a semester and was held in a gigantic classroom; from the stage I could barely see the students in the back. (There were a lot of them back there, for reasons we at present understand.) I had iv stalwart teaching administration: James Benning, Douglas Gomery, Brian Rose, and Frank Scheide, all of whom have gone on to fame. Learning equally much from them as they did from me, I organized the course as a survey of motion-picture show form and style. That overall structure was the first rough cast of Film Art.

By this time there were several books designed as textbooks for such an appreciation course. After reading a few I decided non to apply any. I relied on Perkins' Film as Film, Noël Burch's Theory of Flick Practice, Jim Naremore's excellent monograph on Psycho, and photocopies of essays by Bazin and others. After teaching the course for three years, I decided, at the suggestion of the Addison-Wesley editor Pokey Gardner, to propose it as a textbook. Kristin had by then taught the Intro course with me, had published some articles, and was working on stylistic analysis for her dissertation on Ivan the Terrible. She became my coauthor, start what some have called America's longest report appointment.

From treatise to textbook—and back again?

Although nosotros wrote information technology for the textbook market, I didn't think of information technology as a textbook. With the hubris of a twentysomething, I thought of information technology equally my treatise on picture show aesthetics. I wanted it to be as comprehensive every bit I could get in.

As Perkins pointed out, nearly books on film aesthetics were tied to the idea of the silent film as the pinnacle of film art. Editing was conceived every bit the supreme film technique, and Griffith and Eisenstein were presented as paragons. Admiring both of them and silent picture equally a whole, Kristin and I wanted withal to requite decent weight to "the Bazinian alternative": long takes, camera movements, staging, and cinematography in depth were no less significant creative resource. Color, sound, widescreen, and other resource were ofttimes ignored by the older tradition, but they had to be given their due. (At this bespeak Play Time became a touchstone for usa. It still is.) Burch'southward book was especially of import equally a quasi-structuralist revision of Bazinian ideas; I found, and still find, this book inspiring.

Just as important, I thought, was a demand to situate techniques of the medium in a holistic context. While I was pursuing DIY film studies down on the subcontract, I was also reading modernistic literature and the New Criticism that so dominated literary life. For me, The Context Of The Work was everything. The whole would ever nourish whatever technical tactic or local event we might pick out.

Many textbooks still insist that techniques have localized meanings: a loftier angle means that the subject is diminished and powerless. Yeah, except when it doesn't, as we insisted about this shot from Northward by Northwest in the get-go edition and since. ("I think that this is a matter best disposed of from a great height.")

Considering I was interested in the whole film, I was attracted to philosophers of art who balanced a recognition of manner with a recognition of overall class. Thomas H. Munro's Grade and Style in the Arts (1970) helped me with this, but the major influence was Monroe Beardsley's Aesthetics (1958), with its distinction between texture and structure. That stardom meant realizing that films displayed large-scale formal principles, like sonata form in music. What were those principles?

Hence a affiliate on narrative and non-narrative forms. Nosotros adult ideas of narrative out of formalist and structuralist theories. In the first edition, there was a lot more than on narrative than on other sorts. In later on editions, nosotros tried to flesh out some 18-carat not-narrative options: abstract form (Ballet Mécanique and many experimental films); categorical form (e.thousand., Gap-Toothed Women, The Falls); rhetorical class (e.g., The River, Why We Fight); and associational class (e.g., A Moving picture, Koyaanisqatsi, and many "moving picture lyrics").

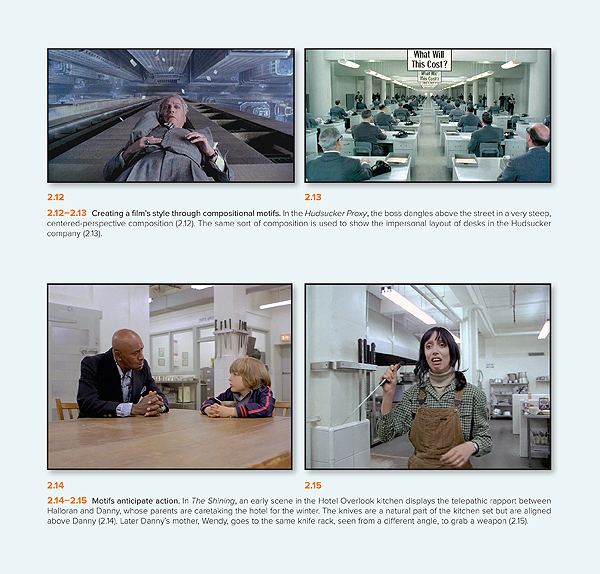

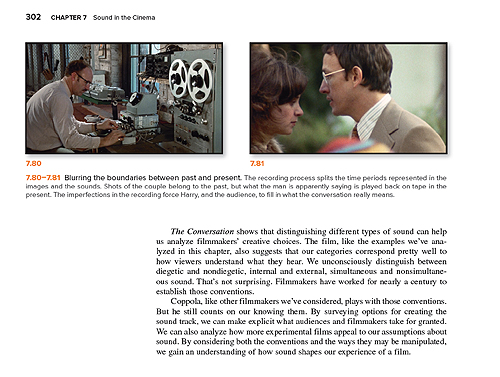

In didactics Introduction to Motion-picture show, I noticed that many students hadn't been exposed to bones aesthetic concepts like form, style, theme, subject matter, motifs, parallels, and the like. The former New Critic in me rose upwards. I thought these ideas and terms, being central to the aesthetics of any medium, needed to be in the volume besides. Hence a chapter "The Significance of Pic Form." (In a higher place is a page illustrating visual motifs: perspective design, props gear up upwardly to be used later.) Some have taken this affiliate as a manifesto of a "formalist" perspective, but actually the ideas in the chapter are ingredient to any aesthetic position whatsoever. Every analyst volition trace patterns of development in a motion-picture show, or weight the opening strongly, or notice thematic parallels. These are bones tools for thinking and talking almost whatsoever art.

But I wasn't a New Critic 100%. I've always been interested in going beyond the artwork itself to look at the artistic traditions and institutions backside it. Because a film results from a concrete procedure of production, I thought it important to include a chapter on how a motion-picture show gets made. That topic was the first one in our introductory form; the reading was Truffaut'south "Periodical of Fahrenheit 451." Starting Movie Fine art with a chapter on product served to innovate film techniques in a physical context, and it showed how what appeared on the screen was the result of choices among alternatives. We thought, and still think, that this chapter might engage students who want to pursue filmmaking themselves. It's been gratifying to acquire that some production courses use the book.

The concern for practice led us to specify, for the first time in an introductory studies text, the 180-degree system of editing, the 4 basic dimensions of flick editing, a layout of what you lot can practise with sound in relation to space and time, and other practice-based concepts. We tried to systematize what filmmakers do, even so intuitively. Sometimes we popularized terms that were already specialized (e.g., "diegesis" for the world of a story). Sometimes nosotros had to invent terms for things that didn't accept names (e.g., the graphic match in editing). Sometimes we had to choice 1 usage of a term that was used in several ways (east.grand., jump cut). Sometimes nosotros had to make distinctions that weren't explicit in the literature, such as the deviation between story and plot, or deep-infinite staging and deep-focus cinematography.

Creating such labels may seem pedantic, but once we take a proper noun for something nosotros can notice it. Kristin and I believed that a study of picture aesthetics has to be alive to all creative possibilities we tin can imagine. For case, in probably the toughest function of the book, nosotros sought to business relationship for all the possible creative choices involved in relating sound to narrative time. Maybe some options are rare, but they practise exist equally office of cinema, and they may yield powerful effects.

Aesthetics in history

Beetlejuice.

Other features of the book flowed from these central ideas. Considering of the emphasis on holism, nosotros added sample analyses every bit well—studies of unmarried films that showed how the various techniques worked together with overall form. The urge to exist comprehensive led the states to devote more than space to experimental, documentary, and animated film than was common in introductory textbooks. And, since this was a period in which academic film studies was making important discoveries, Kristin and I idea it of import to discuss the concept of the "classical Hollywood picture palace," a powerful tradition of story and style that students would have often encountered. Past the fourth dimension Moving picture Fine art 1e was published, we were planning what would become The Classical Hollywood Cinema, written with Janet Staiger.

So Picture Art became a treatise. Was information technology a textbook? I wasn't sure. I thought the publisher might plow it down. Fifty-fifty though it incorporated examples that were educatee-friendly, it had a daunting infrastructure. I idea faculty might observe information technology also complex for almost classes. Had information technology been rejected, I would probably accept tried to publish it as a costless-standing book like those 1960s treatises.

Surprisingly, all these features of the book were acceptable to the readers to whom Addison-Wesley sent the manuscript. Nonetheless, many had a big objection: There was no chapter on motion-picture show history, and that would impale it for them.

I hadn't included a historical unit in my introductory course because there wasn't time. As well, our section had a parallel form surveying moving-picture show history. But Kristin and I were happy to accede to the readers' request. We took as the chapter'south motto a line from art historian Heinrich Wölfflin: "Non everything is possible at all times." (You see what I mean about complexity; what movie textbook quotes Wölfflin?) The judgement simply ways that the artist, in this instance the filmmaker, inherits a express ready of possibilities of class and style, to which she can respond in a broad just not infinite diverseness of ways. We (mostly Kristin) used the concepts we'd developed in the book to trace a series of major traditions and schools, from early movie theater through to the French New Moving ridge. Nosotros've since enhanced that business relationship, bringing it up to date with the New Hollywood and Hong Kong picture, and accentuating the standing importance of older trends–signalling, for instance, German Expressionism'southward legacy in horror comedies likeBeetlejuice, to a higher place.

We know that we owe a lot to luck of timing—to being at the commencement of academic moving-picture show studies—and to the many, many teachers who have offered us suggestions for improving the volume. One advantage of doing a textbook is that you lot can meliorate it incrementally, something not possible with a scholarly volume that will probably see simply one edition.

We're gratified that the result has continued to exist useful. We go along to run across teachers and students who tell united states of america they've benefited from it. Filmmakers, too, from Pixar artists to experimentalists. The volume has been given a couple of dozen translations. Other textbook writers have institute our concepts, organization, terms, and examples persuasive. (When I see how closely some hew to our book, I don't know whether to experience gratified or depressed.) We accept this wide acceptance as a sign that nosotros contributed something fresh and valid to our agreement of cinema. Maybe we did write a full general aesthetic treatise later all—non the first, not the last, but i that remains illuminating and in some respects foundational.

Humblebragging, minus the apprehensive part

From edition to edition our basic framework has been retained, but information technology's flexible enough to be revised and fleshed out. Changes in film engineering science (digital cinema, prosthetic makeup, performance capture, iii-D) take prompted us to trace their effects on style. New developments demanded new concepts and names ("network narratives," "intensified continuity"). Our research for other writing projects gave united states deeper sensation of Asian film, early on movie theatre, ensemble staging, and other subjects we've incorporated into our general perspective. Tough subjects to talk virtually, like acting, have challenged us to come upward with some new ways of thinking about them. We've constitute erstwhile films that we want people to see; we recollect that we should too exist educating taste and getting students acquainted with things beyond contempo releases and cult classics. And of course new films accept been made that need attending—not only because students are aware of them but because the art of cinema continues to grow before our eyes.

The eleventh edition has changes small and large. Of course we've rewritten stretches to brand them clearer or sharper. We've added new examples from about fifty films, from Nightcrawler and Brave to Zorns Lemma, Searching for Sugarman, The Act of Killing, and Beasts of the Southern Wild. The biggest changes involve a recast section on 3D, with discussion of Business firm of Wax and The Life of Pi; a new section, "Flick Manner in the Digital Historic period," with concentration on Gravity; a new department on genre devoted to the sports picture (with Offside as a key case); and, equally the cover tips yous off, an extended analysis of Moonrise Kingdom, a favorite on the weblog also (here and hither).

Under Kristin's direction, with the kind cooperation of Criterion, we have added new video examples to the Connect online platform. Those include sequences from L'Avventura, Ivan the Terrible, I Vitelloni, and other major films, with voice-over commentary by one of u.s.a.. In improver, our production guru Erik Gunneson has made a marvelous demo explaining sound mixing techniques.

In all, we're very happy with the way the book has turned out. The pictures are vibrant, the blueprint is crisp, and in that location are new marginal quotes and links to blog entries. As ever, the blog offers annual suggestions for integrating information technology with courses. We've also put up some video lectures on this site, listed on the left of this page, and of course people are costless to use them in classes. A couple weeks ago we gathered some key blog entries effectually a key topic in Film Fine art, the nature of classical moving picture narrative. Finally, as nosotros've proceeded through many editions, we've had to cut several analyses of particular films. Simply those are still available every bit pdfs online; most recently,nosotros posted our in-depth study of audio and narrative in The Prestige.

All these supplementary materials are attempts to illustrate and develop the ideas nosotros're proposing in Film Fine art–and to practise so in a articulate, physical way. As we say in our introduction to the edition:

In surveying moving picture art through such concepts as grade, style, and genre, we aren't trying to wrap movies in abstractions. Nosotros're trying to bear witness that in that location are principles that tin shed light on a multifariousness of films. We'd exist happy if our ideas can help you understand the films that you enjoy. And we hope that y'all'll seek out films that stimulate your heed, your feelings, and your intelligence in unpredictable ways. For united states of america, this is what education is all about.

Nosotros remain grateful to the colleagues, instructors, students, and general readers who have supported what we've tried to practise.

Every bit office of McGraw-Hill Teaching's multimedia publishing plan, Motion-picture show Art 11e is available in many formats, including a print edition and digital editions that meet the needs of entire film courses or contained readers.

*Every bit ever, instructors, students, and general readers can go a print copy of the new Motion picture Art. It is bachelor in bound or binder-ready form. Instructors who wish to order a custom print edition may include the bonus chapter on moving-picture show adaptation.

*If you teach a course using Moving-picture show Fine art, you can cull the digital option:Connect. Connect is a course-oranization tool that enables faculty to assign reading, submit writing, take assessments, and more. Connect gives students access to a subscription-based digital version of the book chosen SmartBook. SmartBook has the Benchmark video tutorials embedded, plus the power to assign all of the pre-built quizzes, practice activities, and other features. SmartBook includes the new chapter on film adaptation, along with additional material including our suggestions on writing a disquisitional analysis of a film, and additional bibliographic and online resource.

Connect can integrate with your school's learning management system, making it piece of cake to assign and manage grades throughout the semester. Students volition get admission to SmartBook for 6 months; an instructor business relationship does non expire, so y'all tin can reuse your Connect course semester-later on-semester. Instructors may contact their local McGraw-Hill Higher Teaching representative for more information at http://shop.mheducation.com/store/paris/user/findltr.html. (Enter your state and schoolhouse to find your rep's name and email accost.)

*If you desire to read the book independently in digital course, y'all may choose standalone SmartBook. This version does not incorporate Connect's form-administration supplements. The Benchmark Collection video examples are embedded in the SmartBook for you to admission any time throughout the subscription menstruum. Students tin can opt for the SmartBook in place of a printed text, fifty-fifty if their instructor is not requiring Connect.

For more information: The buying options are explained hither in general and the choices pertaining to Film Art are listed here.

We're grateful to our editor Sarah Remington, as well as to Susan Messer, Sandy Wille, Dawn Groundwater, and Christina Grimm, for all their help on this edition!

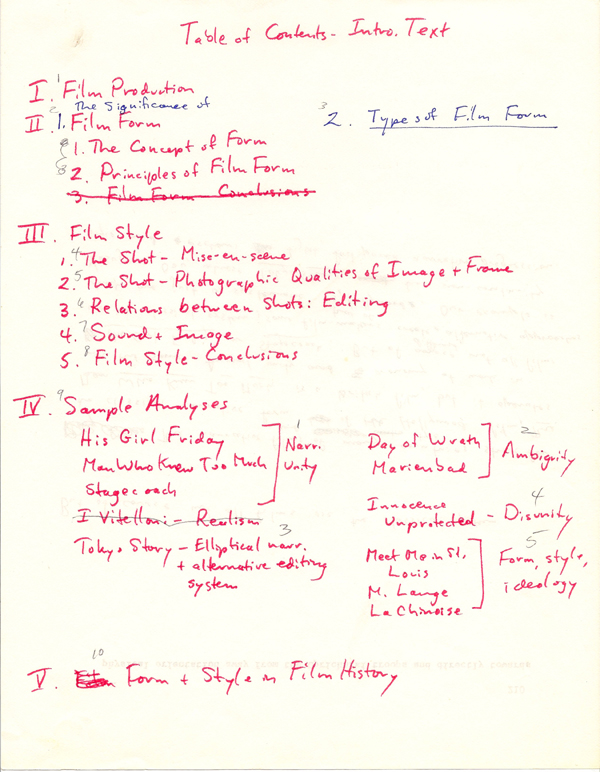

Kristin'due south 1977 affiliate outline for the kickoff edition of Picture show Art.

This entry was posted on Tuesday | February 2, 2016 at 12:52 pm and is filed under FILM ART (the book), Readers' Favorite Entries. Responses are currently closed, just you tin trackback from your own site.

Source: http://www.davidbordwell.net/blog/2016/02/02/film-art-the-eleventh-edition-arrives/

0 Response to "Film Art an Introduction David Bordwell and Kristin Thompson 11th Edition 2017 Mcgraw Hill Pdf"

Post a Comment